Last week I discussed the value of segmenting your time into ‘input mode’ and ‘output mode’ in order to stay focused on getting things done. If you talk about input and output with an engineer or a manufacturer, they’ll tell you that a system is what bridges the two – that funnelling input through a system is what produces output.

Last week I discussed the value of segmenting your time into ‘input mode’ and ‘output mode’ in order to stay focused on getting things done. If you talk about input and output with an engineer or a manufacturer, they’ll tell you that a system is what bridges the two – that funnelling input through a system is what produces output.

It’s no different for your individual productivity – you’re going to need a system (or two… or three) to help you turn all of the many inputs in your life into working and final output. Today I’m looking at what such a system would look like at its very core and filling in the gaps with examples from my own system. As always, your mileage may vary. I’m sharing what I do not because it’s a one-size-fits-all solution that will immediately change your life, but because it’s a system that works for me and my reasoning may help you adapt your own system to work for you.

The Inbox

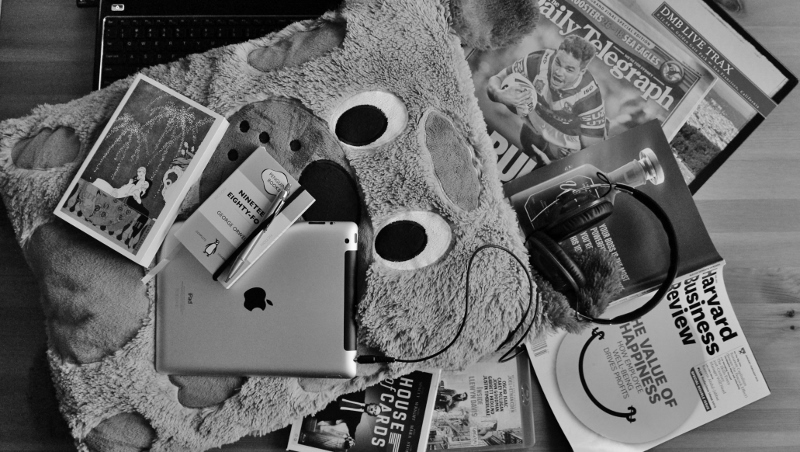

The most important – and central – component of any productivity system is the inbox. Think of your system as a giant funnel through which inputs must pass. The widest opening of the funnel – where everything is captured – is your inbox. It’s best if you have as few inboxes as logistically possible, though it’s not unreasonable to have a few. I operate with three: a physical inbox (which is an actual desk tray in my office) and two digital inboxes (my email inbox and an ‘inbox’ folder in Evernote).

My physical inbox gathers anything that’s a hardcopy – snail mail, business cards, flyers, CDs, and the occasional handwritten note. My email inbox, not surprisingly, captures only email. Just about anything else – including scans of hardcopy items from my desk tray – goes into Evernote.

The trick with inboxes is to keep them empty or as close to empty as possible at all times. This is known as Inbox Zero, a concept popularized by Merlin Mann. If you experience anxiety from feeling like you constantly have too much to sort through, Inbox Zero is your solution and getting there is probably easier than you think.

Getting Things Done (GTD)

Getting Things Done is the name of both a book by David Allen and the productivity system that it outlines. The system deals with your input as it spins toward the bottom of the ‘funnel’, employing filters and triggers through which each piece of input must pass before being actioned or filed away.

Say you receive an email. The first filter for this message asks: does this email require action on my part?

If the answer is no, the email has one of three destinies:

- Trash it

- Save it for possible action (if it contains an idea that might need developing)

- File it away for your own reference

If the answer is yes, the ball starts rolling immediately (and in this order):

- Is this part of a larger project? Define the next action.

- Can you do it in two minutes or less? Do it.

- If not: is this something you should do yourself? Put it on your to-do list or schedule it.

- If it’s not for you: delegate it and make following up your next action.

Again, this structure is what the GTD system calls for – your own system will need to suit your specific circumstances. For instance, I don’t have anybody I can delegate to (without spending money, anyway), so that’s not even an option for me. You may choose to skip the two minute rule and add everything to your to-do list immediately. There are no rules, but considering this framework is a great place to start.

The Assembly Line

Once inputs have passed through your system, you’ll be left with a queue of actions waiting to be converted into output. In this way, you can keep your inboxes at zero without losing track of the things you want to accomplish. My emails don’t disappear – they just get added to my to-do list or they get filed away. Gmail is great to this end, as everything you ‘archive’ remains searchable and easy to find, so there’s really no need to bother with folders or labels (though, again, that doesn’t mean you can’t).

It is at this stage that you can switch into ‘output mode’ and really start getting things done. Knowing yourself and your tendencies is key here. If you like to start with the big, annoying task and get it out of the way, do so. If you like to work your way up by knocking out the easier things first, go right ahead. The important thing is that you stay focused on the task in front of you. When in ‘output mode’ there is no input allowed – no email, no social, no television. If you don’t really feel like switching into output mode, your list of actions and tasks offer a great way to trick yourself by making the question less about should you start and more about where will you start.

It’ll take some time, but once you install and learn to trust your system your inputs will be regularly converted to outputs and your system – along with yourself – will be effortlessly firing on all cylinders.

Leave a Reply