Category: Notes

Being what most would simply call ‘blog posts’. Quick posts [usually] about a single idea.

-

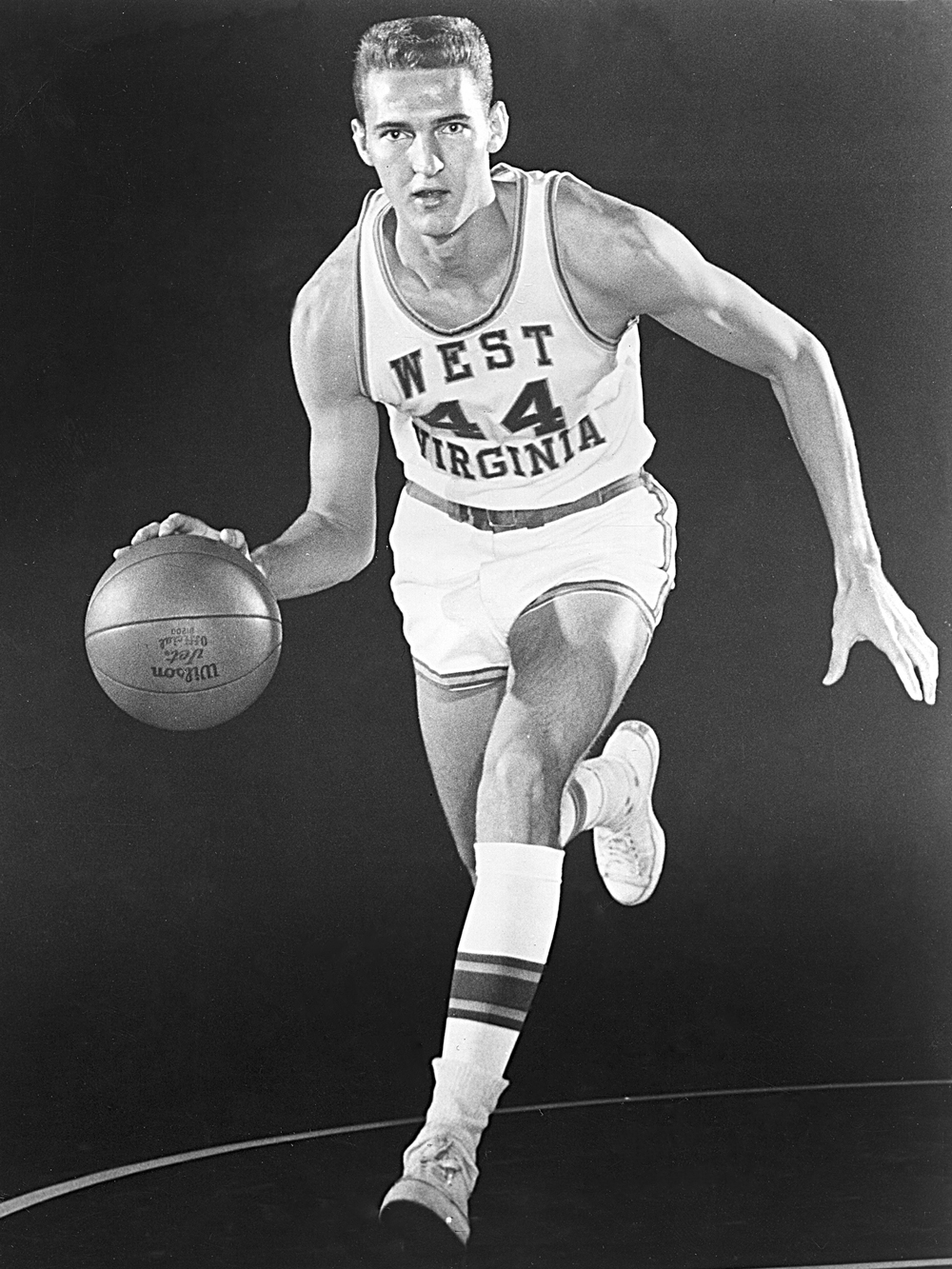

Remembering Jerry West

You knew him as the silhouette in the NBA logo and one of the greatest to ever play the game; I knew him as West Virginia’s favourite son and a personal hero. However you knew Jerry West, the news of his death has likely touched you deeply. There have been two times in my 39 […]

-

A Great Cup of Coffee

I am a lover of coffee, though the origin of this love is difficult to meaningfully trace. While working the most romantic of the various jobs I’ve held in my life — cinema projectionist — in the summer between my Junior and Senior years of college, I was handed my first cup of coffee on […]

-

Ten Years of ToVa

On this day ten years ago, I launched this blog: Toward Vandalia. That’s me (in my younger and more impressionable days) in the photo above, smiling at Rupert, who helped me with post photos in those early days of the site. In early 2023, I wrote a post outlining how the blog has changed through […]

-

When Does the Work Day Begin?

We recently relocated to another suburb of Sydney – one which is farther away from the CBD (where I work) than our previous home was. My commute used to involve only an 11min train ride, which never afforded much of an opportunity to read. Not only am I a slow reader (so I might get […]

-

A Silly Little (Very Important) Photo

I snapped this photo five years ago today. At first glance it is wholly unremarkable. However, it’s assumed unexpected – and evolving – importance to my work over the years. It will be immediately familiar to anybody who has seen me present on design thinking. I initially stopped to take this photo because the scene […]

-

An Open Letter to West Virginia University President Gordon Gee

President Gee, I am distressed by virtually every proposed element of the West Virginia University “Academic Transformation” as announced by the University on August 11. These proposals include the elimination of the MS and PhD Mathematics programs; the discontinuation of all World Languages, Literatures, and Linguistics programs; the elimination of the MFA Creative Writing course; […]

-

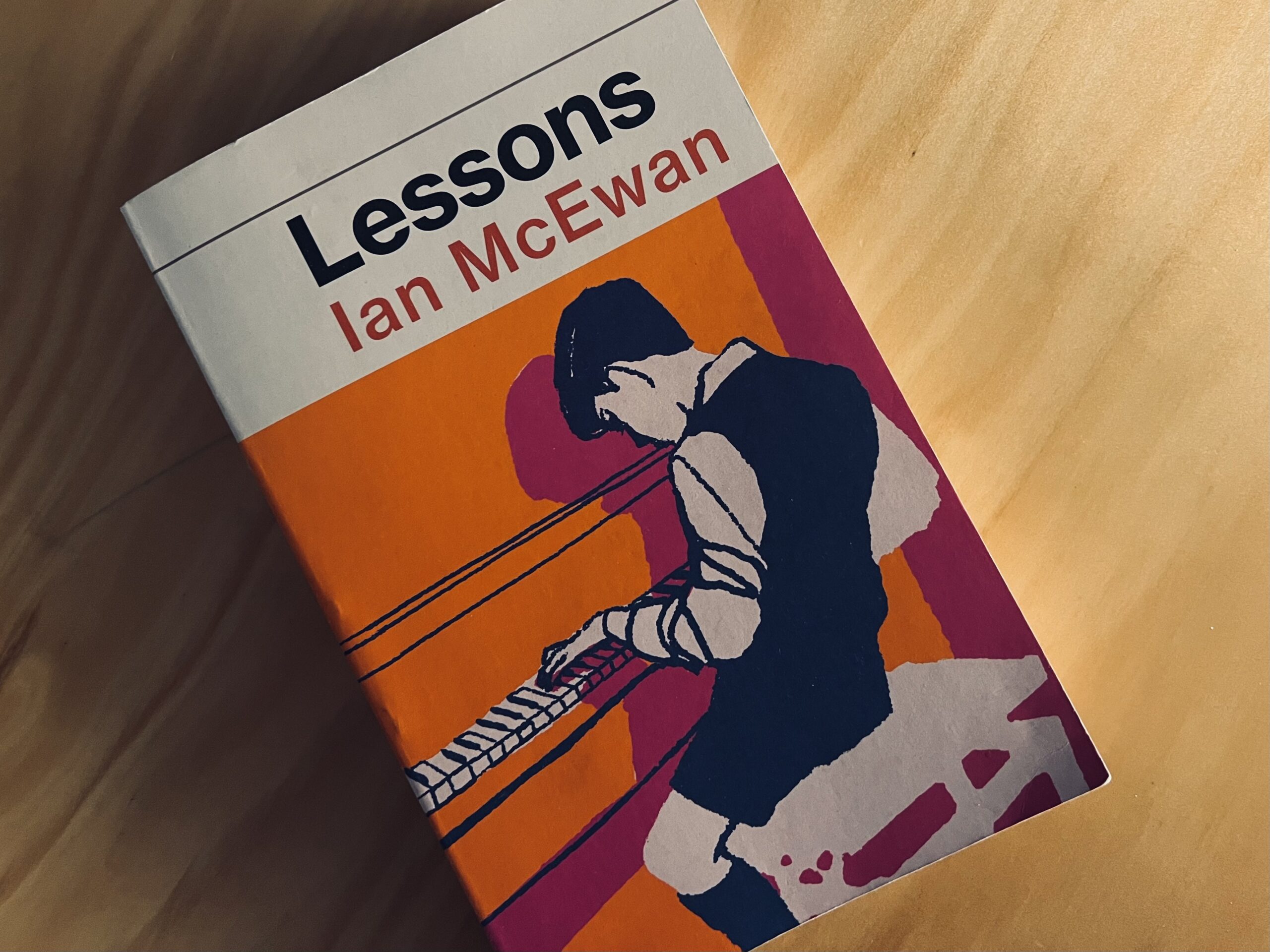

Bookshelves Lined With Your Personality

I don’t get to read much fiction these days. As an academic, I read more non-fiction than most people (yet somewhat less than I’d like to read). Unfortunately, I can only read so much in any given day before I hit a point of diminishing returns in regard to my ability to engage with and […]

-

Welcome To The Party, Pal

Hello. It’s been a while, hey? The holiday season afforded me time and headspace for some long-overdue personal reflection, and this post is one result of that reflection. This site – Toward Vandalia – has been around for nearly nine years. In that same time, my life has seen some major transitions and changes: […]

-

The Final of Many Endings

Today was the ceremonial end of a very long journey. My son was not yet born when my PhD was conferred last year, but the delayed nature of graduation ceremonies in the pandemic meant that he was able to join in on the fun (as a 15 month old!) along with my wife. I was […]

-

Cliffs of the Pacific Coast Highway

November 2016 // One of many beautiful sunsets The Girl and I caught along the Pacific Coast Highway in 2016. Follow me on: 500px // Instagram