I have always felt – and will always feel – a connection to my home state of West Virginia. It’s very much an organic connection to the land; the mountains. Yet, the impetus for this connection is one of fate. As Ron Currie writes in Everything Matters!, who we end up taking out a mortgage with is largely an accident of geography and economics. It stands to reason that any children which result from such an accident stand a good chance of enjoying that same geography (and are almost guaranteed to share the economics). Indeed, I was born in Wood County, West Virginia, as my parents were, and as their parents were. My connection to the land is the product of the latest generational output of this cycle of destiny and yet the accidental origin of that connection does little to dilute the potency with which it perpetuates. I might have migrated to Australia in 2009 but I am what I am, and that’s West Virginian.[note]As my relocation to Australia would suggest, the generational cycle of producing Wood Countians will likely cease with any children that The Girl and I might have one day. Their Australian-Appalachian heritage will be a complex one to evolve into, but they’ll likely prove to be fascinating case studies for linguists and speech therapists.[/note]

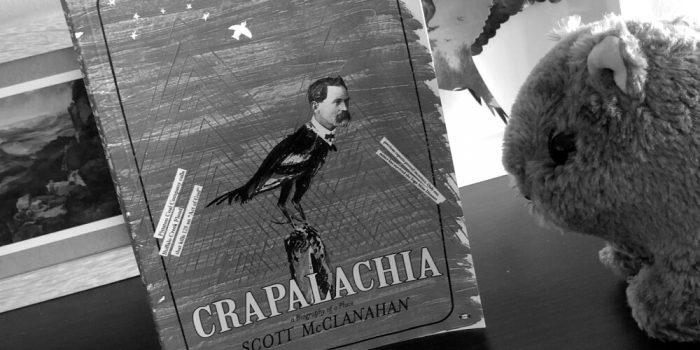

The author of Crapalachia, Scott McClanahan, likewise is what he is, but that ‘what’ is somewhat difficult to ascertain. He was born in West Virginia and he lives there now – this we know for sure – but his connection to the land is difficult to triangulate. Perhaps this is because he writes of the West Virginia landscape – the mountains, in particular – with an awe that seems to drip with resignation. He writes of how his childhood friend Bill tried to teach him and his friends about the mountains that surrounded them – their names and elevations – but not one of them cared to learn about where they were from; where they were. He writes of coming to regret this in adulthood, but the resulting interest appears to have come on a little too late.

McClanahan seems to wish either that West Virginia were some other place, or that his own accident of geography and economics had rendered him from some other place. Either way, there is a meaningful disconnect between what he is and what he wishes he was that seeps into this novel / memoir / journal. The feelings are real, and the prose that conveys those feelings is capable – in momentary heights – of breaking your heart (“I told her I was putting blankets in the trees for our children, so that no matter where they went – they would always be home.”), but the target is unclear. In this way it sometimes reads like a love letter to a girlfriend he can’t quite remember, or who maybe never existed, or who maybe he never really loved.

None of this is problematic in a general way, of course. There is no right or wrong way to skin this particular cat. I wanted to like Crapalachia and I largely did. Stylistically it is memoir in the way that Frederick Exley’s A Fan’s Notes – one of my favorite books – is memoir. That is: it’s so exaggerated and fictionalized that it’s really closer to being a novel. Exley never shied from that fact (he declares the fictions at the outset) and neither does McClanahan (who uses an afterword to roll out an itemized list of the liberties he took). Were Crapalachia not about the place that geography and economics destined my soul to be forever linked to, I likely would love the book without reservation. But it is, and so reservations have manifested.

Writing about your home is a tricky proposition. The many ways in which such an endeavor is fraught with peril have long made me reticent to write of West Virginia in any general way. I’ve always kept it personal, hoping that leaning explicitly and overtly on my own, very individual experience would render my depictions of the state unassailable by those who don’t share my perceptions. The love-it-or-hate-it nature of the commentary around Crapalachia would seem to suggest that my fears are justified.

The book initially popped up on my radar while I was reading up on Breece D’J Pancake. Pancake resented the way that West Virginia – also his home state – was depicted in popular writing, and he set about crafting stories that would correct this deficit of authenticity. By virtually all accounts, he succeeded, and his single published work (a collection of short stories) has developed something of a cult following among readers and writers (not unlike the following A Fan’s Notes enjoys). Somewhere in the midst of reviewing this ongoing commentary, I saw Crapalachia put forward as a modern work that achieved the same authenticity that Pancake aimed to deliver.[note]Pancake had a way of writing fiction that considered the layering of time, in both a generational and prehistoric sense. I tend to view the world around me in a similar way – imagining the way that the world looked in yesteryear; what it might look like after I’m dead and gone. McClanahan does the same in Crapalachia: “And as we drove through the holler I could see the whole place. There was a moment when it felt like it was 1930 and I was traveling through time. I could see the mine. I could see people walking. There were houses everywhere.” Is it something about being from the mountains that makes one prone to considering their surrounds in this way?[/note]

So it was that I cracked the spine[note]Just kidding – I would never actually crack the spine of a book. I’m so careful with the external condition of my books that the ones I’ve read appear as pristine on the shelf as the ones I haven’t touched (on the inside they are scribbled to death but that’s on the inside, you guys). Ask The Girl about the time she accidentally cracked the spine on one of my paperbacks. Or maybe don’t.[/note] on Crapalachia under the influence of high expectations of authenticity… and the touchiness about my home state that is the birthright of all West Virginians. Both were ultimately activated.

The impression that I get from McClanahan (from this book as well as a few interviews with and depictions of him) is that he wanted to deliver an authentic tale of life in Appalachia. This much is apparent from the aforementioned list of liberties that he took with the truth; the reconciling with the factual people and stories that were woven into the tale of this book. In many cases this list is apologetic. McClanahan states that the stories which ultimately became Crapalachia went through many forms. He stops short of saying that all of this reworking involved so many turns that he lost track of his destination.

Ultimately, McClanahan might have wanted to deliver an authentic Appalachian story – perhaps even for the same reasons that Pancake wanted to – but the apparent disconnect between McClanahan and the land seems to have prevented him from doing so. The story isn’t inauthentic, exactly, but it is peopled with amalgamations of real people who are rendered unbelievable by said amalgamation. All of the themes in the book ring painfully true – the obsession with death, the difference in perception of farmers vs. miners, the desire to escape, the bone-deep boredom – but their presentation here is authentic in the way The Simpsons is authentic. Sure, it’s made for socially-conscious adults, but it’s still a cartoon.

The danger, of course, is that Crapalachia[note]Even the title – Crapalachia – is damning. When one is proud of their home, one tends not to call it ‘crap’. McClanahan attempts to let himself off the hook for the title in the afterword, but of course there would be no hook to let himself off of had he not put himself on that hook in the first place.[/note] is seen by ‘outsiders’ as being essentially authentic. These are the non-natives who sing Take Me Home, Country Roads at karaoke and never consider the tragedy that finds the narrator of the song loving a place so much and yet ostensibly living elsewhere.

The authentic West Virginia is – among many, many other things – one where ‘Big Coal’ has taken advantage of a work force – of a people – for so long that those same people now believe not only that it’s the only work they deserve, but also that it’s the only work they want. The fact that one’s view of this phenomenon as inherently good or bad is measured on a wide spectrum underscores why it is difficult to write about West Virginia in a way that won’t offend somebody. You’ll note that I’m leaving my position on the matter deliberately vague. The fear is real.

McClanahan has seen these same things. Indeed, he grew up in the thick of coal country whereas I grew up on the fringe of it. He shares similar thoughts about coal in Crapalachia but he is careful about where to point his finger when doling out blame. He appears to share my fear of offending somebody; anybody. Unfortunately, this leaves the reader to fill in the logical blanks and it is his characters who end up copping the blame. For instance, the line “…only poor people are desperate enough to work in a hole and then thank [G]od that they have a job working in a hole” presents a chicken and egg dilemma – which came first: the mining company or the poor/desperate person? – without positing an answer.

The troubles of West Virginia are thus presented by McClanahan as being natural; perhaps God-given. That he might be right is neither here nor there – the danger is that the decision is delegated not to West Virginians exclusively (I can say this from experience: West Virginians rightfully believe that we are the best judges and defenders of our own misery) but to everybody. Once again, the state has been left to the mercy of outsiders and if history has taught us West Virginians anything, it is that this mercy will not be forthcoming.

Leave a Reply