Category: Essays

Longform essays on a wide range of topics.

-

Living In The Romantic Present

People have always told me I think too much. The accusation didn’t make much sense to me when I was a teenager. My view of the matter at that time lacked nuance: didn’t we all think the same amount, I wondered – and didn’t we do that thinking during every waking moment of our lives? […]

-

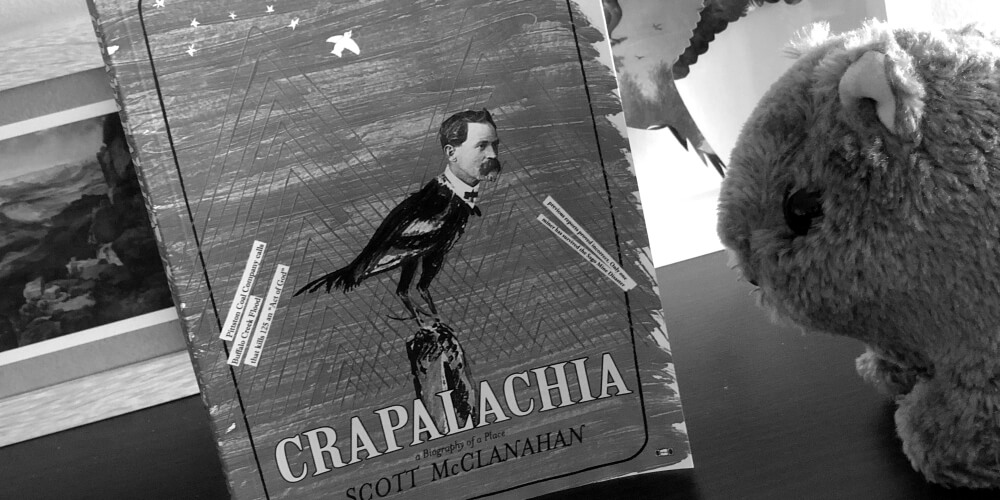

One Man’s Appalachia Is Another Man’s Crapalachia

I have always felt – and will always feel – a connection to my home state of West Virginia. It’s very much an organic connection to the land; the mountains. Yet, the impetus for this connection is one of fate. As Ron Currie writes in Everything Matters!, who we end up taking out a mortgage with […]

-

Time Well Wasted

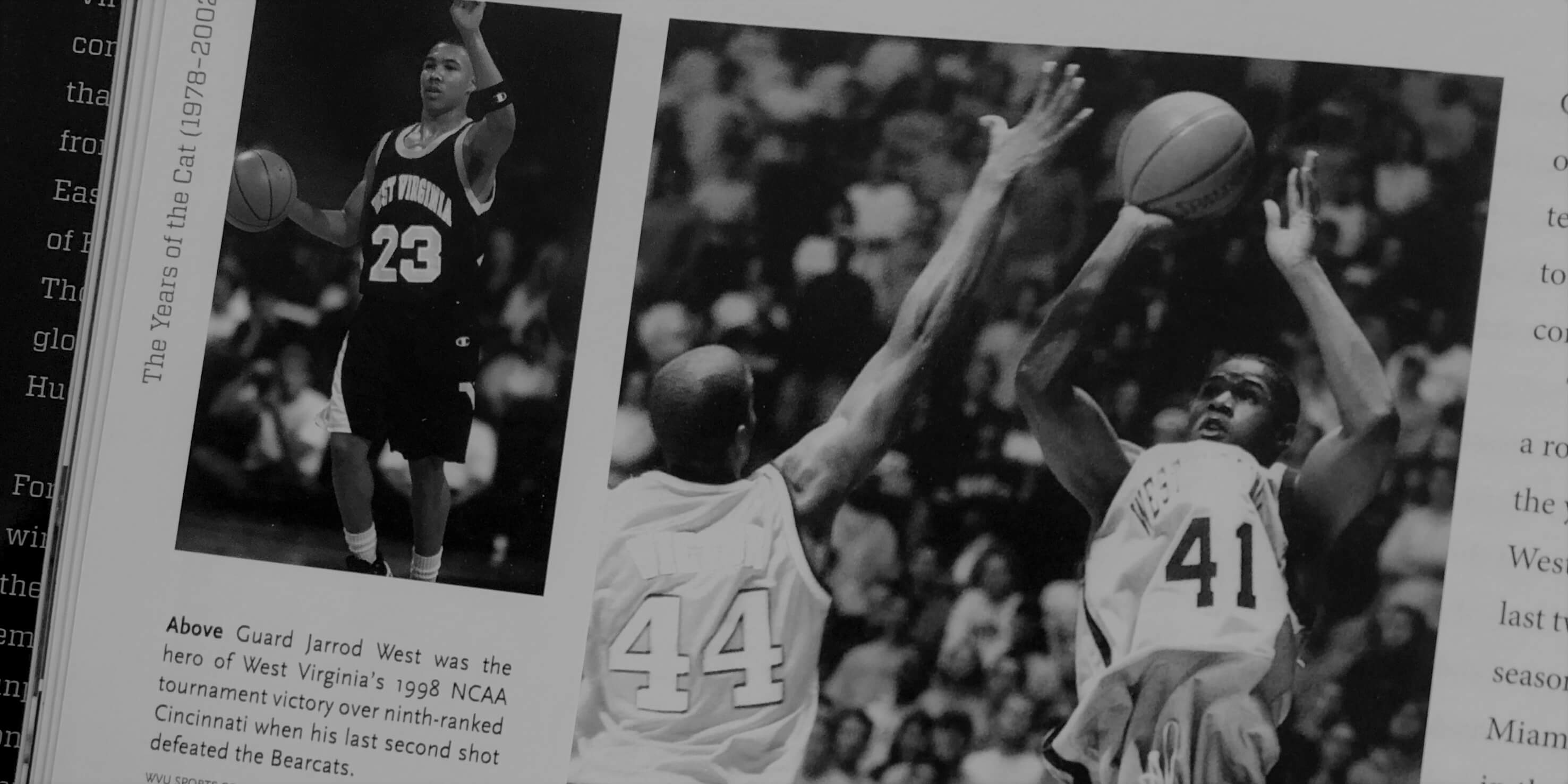

My dad told me I was wasting my time. My West Virginia University Mountaineers were about to face off with the University of Cincinnati Bearcats in the second round of the 1998 NCAA basketball tournament. Admittedly, the prospects were not good. Cincinnati was the number two seed in the region, WVU was the number ten […]

-

A Slow-burning Socio-economic Horror Story

Orlando is a romantic yet transient place. I lived in or around the city for a period of two and a half years after graduating college and in that time I only ever had a meaningful relationship with two people who were from there; Orlando born-and-raised. Everybody else who crossed orbits with me was – like […]

-

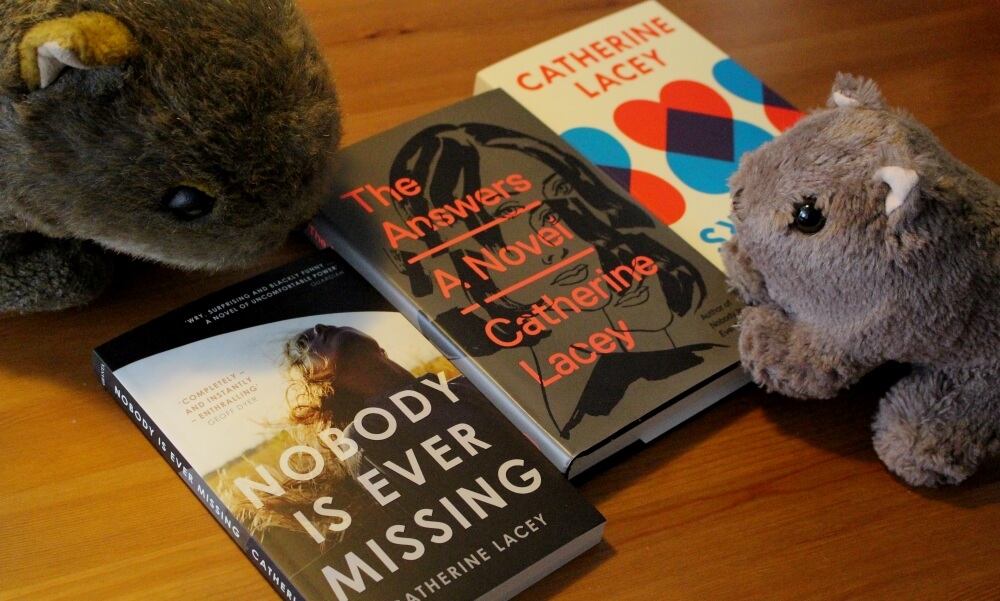

Catching Catherine Lacey

After a recent and extended excursion to the USA, The Girl and I have been back in Australia for as long as we were away – about six weeks. Unfortunately, the six weeks spent travelling the USA were also six weeks spent very much with each other, whereas the six weeks we’ve been back in Australia […]

-

Ali Barter And The Listlessness Of Being

Sometime in early 2016 I was sitting in Wheat Café in Newtown when I heard a catchy tune cascading from the speakers inside. It had everything that initially attracts me to new music: unique vocals, face-melting guitar and a clean structure that builds to an explosive finish. It turned out to be Far Away by Ali […]