My dad told me I was wasting my time.

My West Virginia University Mountaineers were about to face off with the University of Cincinnati Bearcats in the second round of the 1998 NCAA basketball tournament. Admittedly, the prospects were not good. Cincinnati was the number two seed in the region, WVU was the number ten seed. The Bearcats roster featured players with one foot in the NBA while the Mountaineers were a largely unknown bunch who were just happy to still be playing in March. The pundits on ESPN figured that Cincinnati had a real shot at winning the National Championship, while WVU merely had an opportunity to play a basketball game that day.

Thirteen years old and alone on the couch in the living room, it seemed that I was the only one foolish enough to think we even stood a chance.

–

I was born in West Virginia, which means there are photographs of me as a baby adorned in the ‘Flying WV’ – the logo of West Virginia University. Beyond such social indoctrination, my earliest memory of any kind of proper allegiance to the old gold and blue is a fuzzy awareness that I watched the 1994 Sugar Bowl in which an undefeated WVU football team lost to Florida by a score that lacked even a hint of uncertainty: 41-7. I was nine years old.

Mere months later, my family moved from West Virginia to Kentucky. This relocation landed me in a basketball-crazed state that proved to be a strange garden in which to grow my budding WVU fandom, but the perfect environment in which to weave that fandom into my identity.

The television broadcast of sport events was dictated by region in those days, meaning WVU football and basketball games were virtually never shown in Maysville, Kentucky. That exposure belonged exclusively to the University of Kentucky Wildcats.* My only means of tracking the success (or lack thereof) of my Mountaineers, then, were the brief summaries of their games on SportsCenter, which rarely featured video. I followed the entirety of the 1996-97 college basketball season in this manner, which saw my Mountaineers fall just short of an at-large bid to the NCAA tournament.

Naturally, my middle school classmates were not interested in what was happening with WVU basketball. The University of Kentucky had won the national championship the year before and were favorites to repeat the feat that year. I remember sitting in my seventh-grade history class before the bracket was announced and filling sheets of notebook paper with the accomplishments of my team. My friend did the same thing alongside me, except for his beloved Kentucky Wildcats. His design predicted another UK national championship – mine merely campaigned for WVU to be invited to the tournament. Neither one of us got what we wanted that year.

Being in ‘enemy territory’ has a way of prompting one to entrench even deeper in their beliefs and allegiances, and this was very much the case with my love of all things WVU. The more my classmates wanted to talk about Kentucky basketball, the more I ignored them and focused on what my own team was doing.

A (horrible, horrible) fashion of the time were puffy Starter-brand coats made in bright colors and very-nineties designs. Looking around Mason County Middle School in the late nineties, you’d be forgiven for believing that every student was issued the UK Wildcat version of this jacket at birth. And you’d probably be surprised to see one student wearing an old gold and blue version of the jacket with the Flying WV stitched across the back.

Colors and logos and the apparel on which they’re stitched become flags of sorts, and in that way mine came to identify me not only as a fan of WVU sports but also as a West Virginian in general. My flag was unique and as I grew into a teenager, I began to see the value in that uniqueness; to understand how being from West Virginia had made me see and move through the world a little differently. Even at such a young age, I began to understand the way identities are defined and built. It’s not at all difficult to see how I began to associate such things with the sport teams that drove me to wear those clothes in the first place.

The 1997-98 college basketball season saw WVU receive an at-large bid to the NCAA tournament. Although they were the ten seed (out of sixteen) in their region, I was the most excited I’d ever been about sports. My classmates, of course, were fixated on their UK Wildcats – favorites (yet again) in some circles – but some of them were distracted by the prospects of a school just an hour down the road: the University of Cincinnati. A local boy was on the roster there, and they were slotted in at the same regional two seed that UK had received.

Naturally, regional broadcast schedules (and school…) prevented me from watching our first round game but fortunately the good guys prevailed setting up a match with… the University of Cincinnati.

When I went to school the next day, I was surprised to discover that my classmates actually – finally – wanted to talk about WVU basketball. They wanted to know about the players whose names I had become familiar with over months of getting up at 6am so I could see the whole hour of SportsCenter before school. They wanted to know more about this team that I liked for some mysterious, maybe unknowable reason. My intel was in high demand but it did little to scare anybody. The smart money was on Cincinnati.

Apparently, so was my father’s money. The next day – buzzing with excitement – I could barely sit still as the CBS broadcast switched over to our game. It would be the first WVU basketball game I would see that season. My expectations were high. I wasn’t old enough to process the disappointment of the 1994 Sugar Bowl. Or of the 1989 Fiesta Bowl, which was the de facto national championship game that year. My dad knew those disappointments and had lived through some largely mediocre decades of WVU basketball. When he told me that I’d be wasting my time by watching the game that day, he was probably just trying to help me avoid heart break.

Today I remember nothing about the first 39 minutes and 53 seconds of the game. I remember only the final seven seconds. At that moment, Cincinnati’s D’Juan Baker had just hit a three pointer to put Cincinnati in front by two. This wasn’t entirely devastating – WVU could easily move the ball to the other end of the court in that time and find at least the two points that would send the game to overtime. But this is not what happened.

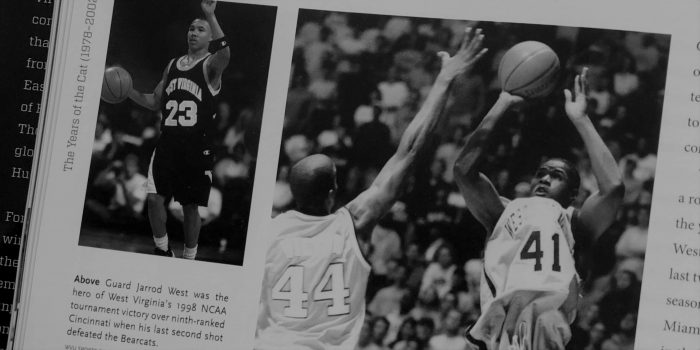

Instead, Jarrod West stopped three steps short of the three point arc and – with over three seconds left – threw up one of the most ill-advised shots I’ve ever seen. Rather than take the extra seconds to drive through a disorganized Cincy defence and live to fight in overtime, West went for the win with a rainbow shot so tall it was a threat to hit the rafters. Instead, it hit the backboard in a spot that doesn’t usually lead to a friendly bank.

It was an ugly shot. An ill-advised shot. Altogether: an unnecessary shot. But none of this matters because – twenty years on – it’s the ugliest, most ill-advised, most unnecessary shot I’ve ever seen go in.

Thirteen year old me lost his thirteen year old mind. The luckiest of sports fans experience many moments like this, but this was my very first. There have been others since. Two of these – a 2003 defeat of #3 Virginia Tech in football and our victory in the 2006 Sugar Bowl, which was the final game of my four years in the WVU Marching Band – took place while I was an undergraduate at WVU. Bob Huggins, the coach of the Cincinnati team we defeated that day, would later come home to West Virginia and lead us to a Big East Tournament championship and the Final Four in 2010**. It would take until 2013 (and an overseas move) for any of my teams to win their respective championship (the Sydney Roosters of the National Rugby League). I’m still waiting for that elusive national championship for WVU.

The week after this game, WVU fell in a close game to the University of Utah, ending their run in the tournament. It would be another seven years before we returned to the tournament in 2005 – my junior year at WVU. I would be in the stands for our first and second round games, the second of which saw another upset of the two seed: Wake Forest.

My family moved back to West Virginia before that 1998 tournament concluded and I found myself quietly cheering for Utah to continue winning, if only to – in some small way – make our prior loss to them somehow more valiant in hindsight. And continue winning they did, running all the way to the championship game before finally meeting their match. Imagine my relief when I went to my new high school in West Virginia the next day and nobody had a single word to say about the team that bested Utah to win that 1998 national championship: the University of Kentucky Wildcats.

–

* With Tim Couch under center, even UK football was interesting at this time. Go figure.

** This story isn’t complete without cheekily noting that Kentucky was the team we beat to advance to the Final Four in 2010. Sorry not sorry, guys.

–

Greg Joachim was born and raised in West Virginia and still has those baby photos to prove he has been a Mountaineer fan his entire life. He graduated from West Virginia University in 2006 (B.S.) and the University of Technology Sydney in 2014 (M.B.A.) where he is now a PhD researcher attempting to maximise the social outcomes of youth sport programs. He lives in Sydney with his wife, Claire.

Reach out to him on Twitter: @gregjoachim